big deal dealers

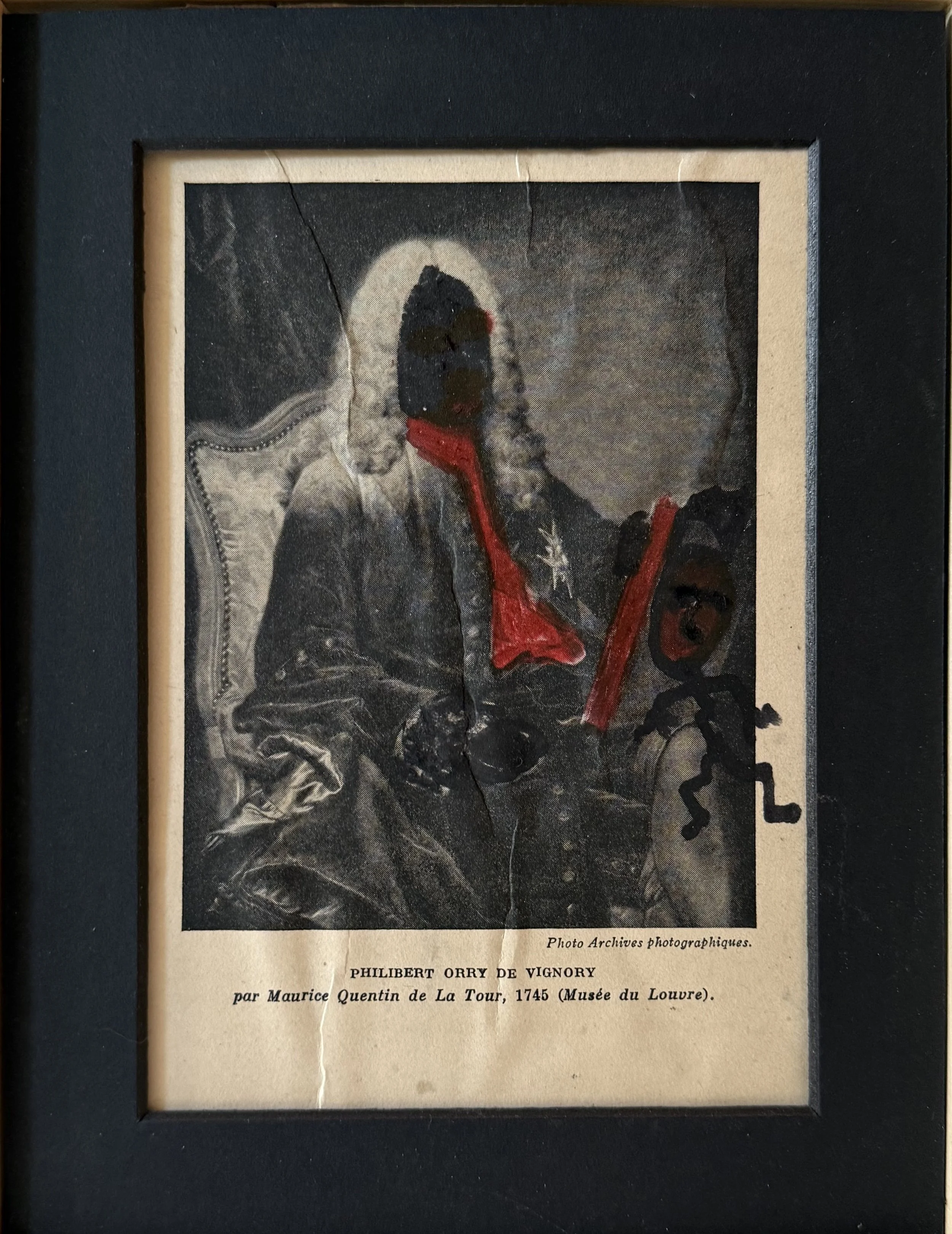

Olivier Bringer. Le conseil du désordre (Philibert Vignory par Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1745), 2019, marker on old book laminated to cardboard.

Evolving galleries

From the 17th to late 19th centuries, the Salon system was the official art exhibition system in France. It was controlled by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Artists submitted works to a jury, which then selected pieces for public display at the Paris Salon. Success at the Salon was crucial for artists' careers, determining commissions, patronage, and reputation.

The Salon system enforced strict academic standards favoring classical themes, techniques, and historical subjects. Artists who deviated from these standards, like early Impressionists, were often rejected. The Salon's conservative control over artistic taste and careers ultimately led to its decline as artists sought alternative exhibition venues. Enter the era of the dealer-agents.

By 1900, dealers and critics had largely replaced the Salon's role in determining artistic success and market value. Dozens of women and men became taste- and career-makers. In fact, there is a retrospective nostalgia for the best-known, historic European dealers, including Heinz Berggruen, Ernst Beyeler, Joseph Duveen, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the Rosenberg brothers, Ambroise Vollard, and Nathan Wildenstein.

In the late 20th century, a “dealer-collector-curator system” emerged as museums and institutions gained more influence in the art market, and as technology become a powerful tool for communication and near-instantaneous gratification. This system reflects art's increasing institutionalization and the rise of museums as cultural arbiters. While critics remain relevant, they are almost bystanders, having less direct market influence than curators and collecting institutions. Instead, collectors—often wealthy ones—now work directly with museums, serving on boards and “pledging” individual works and collections. Dealers and galleries alike coordinate with institutions to build artists' reputations and, by dint of relationships, markets.

Yet, few gallerists and dealers have radically transformed the art business. Most of them are earnest retailers operating on a small scale, usually at one location. Typically, they are single-generation businesses with uncertain futures. Even with the emergence of modern technologies, few gallerists are true innovators. Some have morphed into luxury lifestyle brand builders, creating restaurants, hotels, and retail shops. Others have become book and edition publishers, morphing into online retailers and data farmers. A few have developed immersive experiences, which are frequently difficult to distinguish from other popular, mass audience entertainments.

For linn press, Paul Durand-Ruel, Grand Central Art Galleries, Leo Castelli, and Larry Gagosian are the indisputable innovators of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Paul Durand-Ruel

During his lifetime, Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) profoundly altered the traditional role of the art dealer with his unwavering and absolute dedication to his artists, both financially and morally. A determined and ambitious entrepreneur, Durand-Ruel was a precursor of the international art market, establishing a network of galleries in Paris, London, Brussels, and New York and organizing numerous international exhibitions.

Completely convinced by the talent of the artists he promoted and confident in his role as the defender of their art, Paul Durand-Ruel was able to secure a legacy for the Barbizon school and, above all, the Impressionists. After the death of his father—also an art dealer—Durand-Ruel purchased around 12,000 pictures, including, roughly, 1,000 by Monet, 1,500 by Renoir, 400 each by Degas and Sisley, 800 by Pissarro, 200 by Manet, and 400 by Cassatt. Over forty years, Durand-Ruel became the most powerful driving force behind Impressionism, making it a household name. As Monet would recall in 1924, about two years after the dealer’s death, “Without Durand, we would have died of hunger, all us Impressionists.”

Paul Durand-Ruel

Beginning in 1883, while the Impressionists struggled for acceptance in Europe, Durand-Ruel took his artists’ works to the United States. He tried without great success to promote his artists with exhibitions in Berlin, London, and Rotterdam. In 1885, James Sutton, the director of the American Art Association, brought Durand-Ruel and 300 paintings to the United States, along with an enthusiast endorsement from Mary Cassatt. In the years that followed, Durand-Ruel et Cie staged exhibitions of Impressionist paintings in a number of American cities, including Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Denver, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Using trains and horse-drawn carriage, he also shipped paintings to collectors across the United States

Opening a permanent gallery in New York in 1887, Durand-Ruel began to play a pivotal role in the formation of American collections. Among the paintings he sold to collectors in this country are Degas’s The Ballet Class (Philadelphia Museum of Art), Morisot’s Woman at Her Toilette (Art Institute of Chicago), Renoir’s large-scale Dance at Bougival (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Sisley’s View of Saint-Mammès (Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh).

Durand-Ruel and the avant-garde artists he represented eventually overturned the system in which the French Salons had been the validators of contemporary art. In the process, he developed a new way to display and sell works of art. The art gallery became the forum the introduce the public to then-contemporary art. As the new system developed, dealers would increasingly be the ones who selected works to show, hosted gallery openings, placed works in museums and helped to create prominent private collections. In doing so they gave hefty authentication to the artists they represented.

In short, Durand-Ruel progressively developed a personal and professional philosophy that transformed the art business of the 19th and 20th centuries. His philosophy was based on a few key tenets; to:

Protect and defend art above all else

Exercise exclusivity over the artists’ production

Mount solo exhibitions

Maintain a network of international galleries and relationships

Provide free access to his galleries and his apartment

Promote artists’ work via the existing media

Associate the art world with the finance world.

As a side note, Joseph Duveen (later Lord Duveen) (1869-1939) is often characterized as “the” art dealer to the ultra-wealthy of America’s Gilded Age and as a role model for Larry Gagosian. His success is famously attributed to his observation that "Europe has a great deal of art, and America has a great deal of money." This was something of a reverse Robin Hood strategy. Some of his most notable clients included Henry Clay Frick, William Randolph Hearst, John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan, and Andrew Mellon. He was instrumental in helping these American industrialists build their art collections, many of which later formed the basis of major American museums.

In reality, Duveen began as a merchant of everything from antique silverware, ivory carvings, rare porcelains, period furniture, and Oriental rugs, before selling European masterpieces. He formally set up shop in New York in 1886, following the uptown move of upscale retail from lower Manhattan.

Grand Central Art Galleries

Floor Plan of Grand Central Art Galleries, New York City

Grand Central Art Galleries was a “cooperative” that was established on the sixth floor of Grand Central Terminal in 1922. It played a notable role in democratizing art access in America, though its historical significance is sometimes overlooked. The combination of the gallery’s mission, operations, location, and size had a central role in the development of the New York, if not the US, art market.

The galleries covered 14,000 square feet (1,300 m2) and offered nine exhibition areas and a reception room that was described as "the largest sales gallery of art in the world.” By situatiing itself atop Grand Central Station, the galleries brought fine art into a major public transportation hub. This location choice was strategic, making art accessible to thousands of daily commuters who might not otherwise visit traditional galleries.

The cooperative was founded by Walter Leighton Clark, together with John Singer Sargent, Edmund Greacen, and others. Its mission was to offer notable American artists the opportunity to exhibit their work in the United States without having to send it abroad. The galleries’ innovative business model allowed artists to become shareholders, giving them more control over how their work was displayed and sold, a departure from the traditional dealer-controlled system.

Walter Clark was a visionary businessman, inventor, artist, and philanthropist who divided his time between New York City and Stockbridge, MA. His memoir—Leaves from an Artist’s Memory (1937)—recalled how “one evening a number of artists . . . [met to discuss] their lack of facilities for disposing of their pictures.” He continued, “Painters are really fine fellows, but they are distinctly individualists. Attempts at a mutually helpful organization had been tried a number of times, but each time with the same unfortunate result.”

Clark recalled, “Some one very fortunately called my attention to the attic over the Grand Central Station, which was serving no practical purpose. This attic extended the whole length of the Grand Central Station, facing on Forty-second Street, with a floor space of about fourteen thousand square feet.” The gallery's inaugural exhibition was dedicated to the work of John Singer Sargent, who was a founding member of the organization. “The receipts from entrance fees and catalogues amounted to about forty thousand dollars, twenty-five thousand of which was invested in interest-bearing bonds.” The gallery had continuous exhibitions of members' work, “and important collections of the work of our artist members all over the United States.“

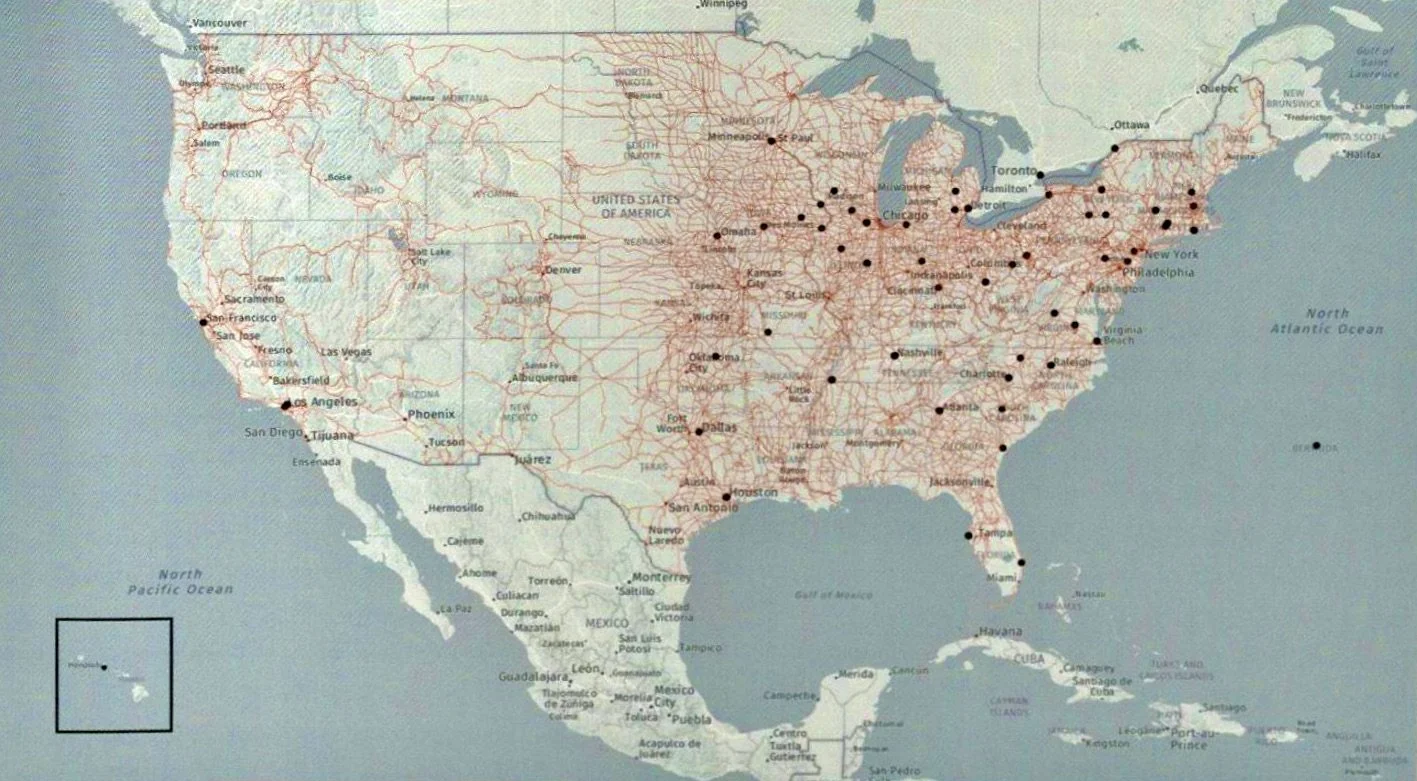

Clark continued, “As the Gallery is [sic] located in a Railroad Station, we are able to have express cars placed at the foot of our elevators. Thus in a very short time pictures can be loaded without any boxing, and can be carried to their destinations quickly and at the least possible expense. These out of town exhibitions have proved exceedingly valuable, and they have succeeded in creating interest in art in various parts of the country where previously attention had not been effectively drawn to the subject [of art]. For instance, in Houston, Texas, they had just completed a new Art Gallery, but there was nothing to put in it. We sent to this gallery about half a million dollars worth of pictures and sculpture, enough to fill the museum.”

Map of known locations of Grand Central Art Galleries national art exhibition campaigns, 1923-39. Cities of exhibitions arc noted with a black dot, and the historical railroad lines are shown with orange lines. Created in 2022 using author data, CARTO, and files by Jeremy Atack, "Historical Geographic Information Systems (GIS) database of U.S. Railroads, 1826-1911 (May 2016)."' Image by and courtesy of Samantha Deutch.

In addition to its main offices, the Grand Central Art Galleries directed several other enterprises. It launched the Grand Central School of Art in 1923, opened a branch gallery at Fifth Avenue and 51st Street in 1933, and in 1947 established Grand Central Moderns to show non-figurative works. The Grand Central Art Galleries were also responsible for the creation, design, and construction of the United States Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

The Galleries were active from 1923 until 1994. By 1934, $4 million worth of art had been sold. In 1958 the Galleries moved to the second floor of the Biltmore Hotel, where they had six exhibition rooms and an office. They remained at the Biltmore for 23 years, until it was converted into an office building. The Galleries then moved to 24 West 57th Street, where they remained until they ceased activity in 1994.

Leo Castelli

Leo Castelli (1907-1999) was a pivotal figure in New York’s post-War art market. He is credited with transforming the post-War art gallery system and creating a new model of art patronage and representation in the mid-20th century. Moreover, he shaped the American contemporary art scene, promoting Pop Art, Minimalism, and Conceptual Art.

After opening his first gallery in New York in 1957, Castelli revolutionized how art galleries supported and developed artists' careers, for example, he provided long-term, comprehensive support to emerging artists, offered artists financial stability through a stipend system, and provided consistent exhibition opportunities. In effect, he treated artists as professionals with sustained career development strategies. Castelli became first to postulate what is now understood as fundamental to commercial consumption: the notion of an artist as a marketable brand.

Castelli was assisted by Ivan Karp, who worked for Castelli from 1957 to 1969. (Karp would open his own gallery—OK Harris—in 1969.) Karp served as Castelli's primary director and, perhaps more importantly, as the gallery’s talent spotter, discovering and promoting pop artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg. Nonetheless, Castelli was not a single-genre gallery. Frank Stella, Richard Serra, Donald Judd, and Bruce Nauman were among the artists who represented Minimalism and conceptual art.

As Castelli transformed New York into the global center of contemporary art, he developed a cohesive network of affiliates—almost satellites—with other dealers in the United States and Europe. These relationships facilitated sales and exhibitions and, most importantly, positioned American contemporary art at the epicenter of an ever-expanding global movement. His collaborations with other art dealers and collectors were crucial. Figures like Irving Blum and Betty Parsons were part of a broader community that influenced artistic trends and helped elevate the status of contemporary art. But Castelli was not compelled like several late-21st-century galleries and competitors to several open brick-and-mortar outposts. His system sufficed.

Equally important, art critics such as Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg played essential roles in promoting the artists associated with Castelli, thereby increasing their visibility and market demand. Likewise curators from prominent institutions, including Alfred Barr from the Museum of Modern Art, contributed to the legitimacy and recognition of the artists showcased at Castelli.

Larry Gagosian, Charles Saatchi and Leo Castelli, St. Barthelemy, 1991 © Jean Pigozzi.

There was a notable exception to Castelli’s “solo act.” Larry Gagosian. Castelli essentially mentored Gagosian, helping him develop relationships with major artists and collectors. It was mutually beneficial. Their formal partnership started in the mid-1980s when they opened Castelli/Gagosian Gallery in New York. This enterprise allowed the younger Gagosian to learn from Castelli while giving Castelli access to Gagosian's aggressive new business tactics and his connections to newer collectors.

Castelli demonstrated that commercial success and artistic integrity could coexist, and he developed a model of art dealing that respected artistic vision and helped artists achieve financial sustainability without compromising creativity. Through his collaborations and innovations, Castelli helped to build a robust infrastructure for the contemporary art market, influencing how art was perceived, sold, and collected during a transformative period in the art market. By promoting the idea that contemporary artworks could appreciate in value, he attracted collectors who were interested not only in aesthetics, but also in financial returns, .

Larry Gagosian

Larry Gagosian (b. 1945) is known to be private about his personal life and early career. Nonetheless, in 2011 and 2022, Kelly Crow published two articles in the Wall Street Journal that clarified Gagosian’s market ascent. More recently in 2023, Patrick Radden Keefe revisited Gagosian’s personal and professional evolution in a nearly 18,000-word profile in The New Yorker, titled “How Larry Gagosian Reshaped the Art World.” While most articles about the dealer are redundant, Keefe’s profile was a timely reminder of Gagosian’s significant contributions to and innovations in postwar art as he approaches his 80th birthday in 2025. (See an extended video with Glenn Fuhrman from 2018, and also print interviews with the dealer in Gagosian Quarterly July 2020 and Spring 2024.)

Perhaps, the 2010 to 2020 decade embodies his most significant innovations In 1999/2000, the gallery expanded internationally, beginning in London. He further benefited from the 2001 retirement of Anthony D’Offay, England’s connoisseur of international contemporary art; deepened his relationship with “super collector” Charles Saatchi; hired ambitious, talented personnel, and expanded into an epic-sized gallery near King’s Cross. London was overflowing with an exceptional number of ultrawealthy, “golden passport” expatriates, including Americans. The market was untapped.

Gagosian pioneered the concept of a truly international brick-and-mortar, branded gallery network. London spurred a convenient springboard to Paris, Rome, Athens, and outposts in Switzerland. He cultivated relationships with Russians via his relationship with The Hermitage in Saint Petersburg and later by two exhibitions in Moscow of staggering quality in 2007 and 2008. Moscow changed everything. He was there first with a platinum brand. Hong Kong would follow.

Gagosian revolutionized the relationship between galleries and the secondary market. While traditional galleries primarily focused on representing living artists, he developed expertise in both primary and secondary (resale) markets. He became known for his ability to acquire and resell important works of art, often working directly with major collectors and estates. This dual focus helped him build relationships with important collectors and establish market dominance. Clients came to him. The gallery’s considerable market penetration in Germany was evidenced by the numerous private collections and museums his team developed. Shrewdly, his art fair inventories were varied and market specific. .

Gagosian’s elevated the standards for commercial gallery exhibitions. They are frequently museum-worthy shows in gallery settings. His galleries were architectural, and the interior spaces have been designed to equal those of museums in terms of scale and presentation. At art fairs, the gallery’s booth mimicked the interior design of his standalone outposts, including paint color and baseboards. He often mounted historical exhibitions that would typically be seen only in major institutions, most recently “A Foreigner Called Picasso," an exhibition organized by Annie Cohen-Solal with art historian Vérane Tasseau.

Gagosian’s artist representation model took suggestions from his historic predecessors—like Durand-Ruel and Leo Castelli—by offering unprecedented resources and market reach. He could provide artists with multiple simultaneous exhibitions on two continents, plus Hong Kong; offer extensive publication programs, and unparalleled access to major collectors worldwide. His approaches to marketing and promotion included producing elaborate catalogs and publications, hosting high-profile events, and creating strong relationships with the press.

Larry was among the first to treat art marketing with the sophistication of luxury goods marketing.