post-war art markets

New York, Weltkulturhauptstadt

Katy Schimert. Icarus and the World Trade Center, 1997-1998, film still.

It is easy to forget that Impressionists and modern masters—Cézanne, Manet, van Gogh, and Picasso, for example—were dismissed or derided early in their careers. There was no overnight acceptance. Their audiences were small. In fact, most of these artists were not even known in the United States until the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the 1913 Armory Show (New York), which later traveled to Chicago and Boston.

Decades later, Duchamp, de Kooning, Pollock, and Warhol challenged conventional art-making ideas, reshaping the contemporary art canon, slowly gaining acceptance. A handful of art dealers and a coterie of upper-middle-class collectors transformed a rather white-glove business into an increasingly dynamic market, which was fueled by the creation of post-War wealth. As art centers, Paris was nearly abandoned, and London remained a cultural backwater until the late 1990s.

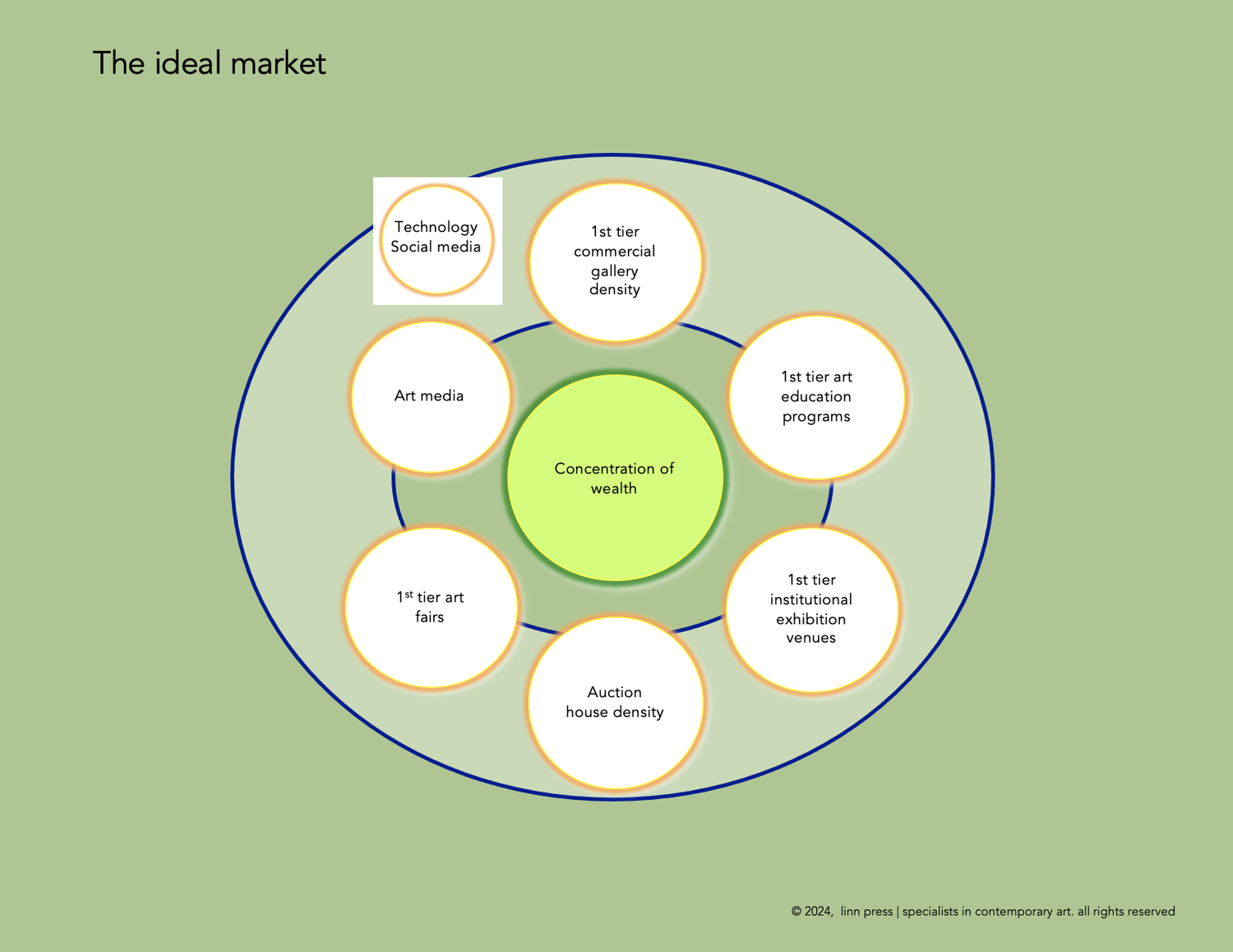

In transactional terms, today’s art market is unquestionably international but is mistakenly termed global. The international art market is New York-centric. London, Los Angeles, and Paris are secondary centers of trade. What makes New York ideal—or, to use the German word Weltkulturhauptstadt, world culture capital—is its perfect balance of artists, educational programs, institutional exhibition venues, galleries, auction houses, art fairs, and media. All of these factors are cocooned in consumer-enabling technologies and social media that frequently glamorize art.

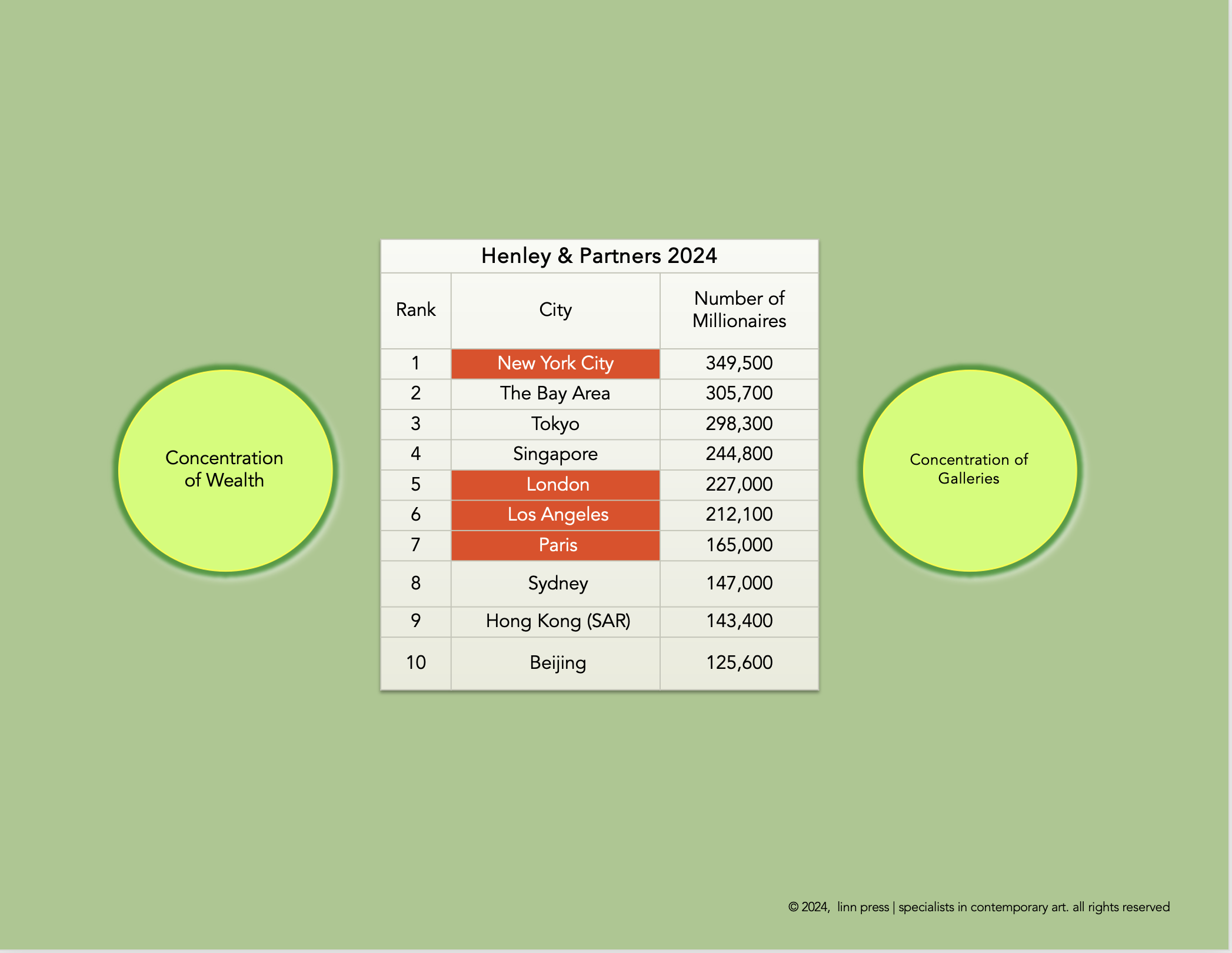

Only New York has all of the essential attributes of an “ideal market,” the most important of which is its concentration of wealth. Apart from New York City, only London, Paris, and Los Angeles have high concentrations of art education programs, galleries, museums, and fairs. In reality, most art markets are regional, if not local. Latins prefer Latin art; Europeans favor European art, and Asians opt for Asian art. These preferences and patterns are especially conspicuous in regional markets, at art fairs, auctions, and galleries. There are many reasons for market insularity, beginning with socio-cultural ones and including all-important economic ones.

The ideal art market.

The hyper-centralization of New York is underscored by the presence of the eight most prominent brand makers that operate in both the primary and secondary art markets. They are privately held, multi-location luxury retailers with large rosters of artists, living and dead. These diverse rosters provide a sort of inventory equilibrium to an industry where artists’ careers and prices rise and fall. Hence, artist (or product) diversity is a necessity in a highly competitive market, which is currently in contraction. These eight galleries further compete with dozens of top-tier, well-regarded galleries in the New York; there are hundreds more with high expectations and aspirations. The majority of galleries are small, almost mom-and-pop businesses, which are frequently under-capitalized, shoe-string operations.

The revenues, expenses, and net debt and profitability of all of these enterprises is largely speculative. They can not be calculated using art fair sales or auction results. Expenses are high. Profit-margins are narrow. The discounts galleries offer are not disclosed, and the commissions they take on secondary market sales are rarely revealed, even to sellers.

Dominant New York galleries.

Concentration of millionaires, 2024.

Since the 2010s, Hong Kong, Los Angeles and, most recently, Seoul have emerged as prominent, but geographically dispersed markets with tens of galleries—oftentimes short-lived—accompanied by auction house representative offices, ballyhooed art fairs, and numerous, often indistinguishable, biennales and triennials. But there is no credible correlation between a city’s wealth (measured in terms of the concentration of millionaires and billionaires) and art market dominance. The Bay Area, Tokyo, and Singapore are not regarded as major art destinations. (In fact, both GAGOSIAN and Pace withdrew from the Bay Area after short-lived presences to concentrate on Los Angeles.) If anything, the greatest competition for conventional art markets has flourished at art fairs and on the Internet and social media, where websites and apps compete for collector attention and money.