market myopia

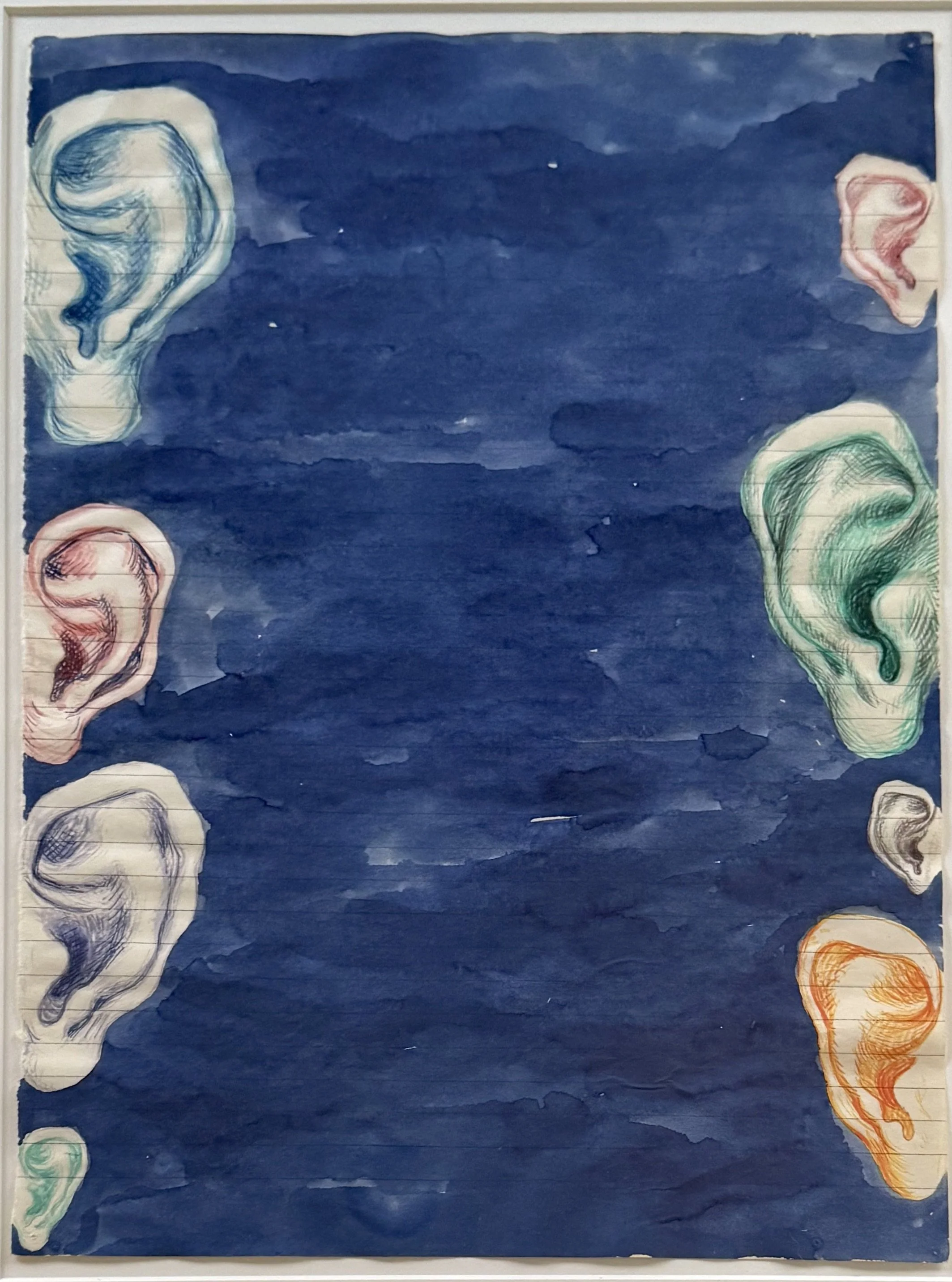

David Moreno. Untitled, 2014, ink and watercolor on paper.

The era of contemporary art fairs began with Art Cologne in 1967. This seminal event (and the hundreds of art fairs that would burgeon in the late 20th century and afterwards), pre-dated FedEx, consumer computers, mobile phones, and digital camera technologies, tools that accelerated communication. Until the 1990s, art criticism flourished in newspapers and respected art media. Museums and galleries were active exhibition venues, stimulating conversation and exchange. In more rarefied collector and dealer circles, ideas and names were circulated, often accompanied by slides or transparencies.

The first real surge of interest in art may have been triggered in 1973 by the now-legendary auction of 50 works by living American artists from the collection of Robert and Ethel Scull, New York taxicab magnates. As Tim Schneider, an art business observer, put it: “‘The Scull sale’, as it is colloquialised today, has since become accepted among many, if not most, knowledgeable art sellers as a moment when the future of the trade arrived.” He continued, “The 1973 Scull auction lives on in art market history as the apotheosis of high-end commerce transformed into a VIP social event. So many spectators arrived that Sotheby Parke-Bernet had to ease them into the building in groups of ten, with most having to be seated in overflow rooms equipped with TVs simulcasting the proceedings in the main gallery.”

Word of mouth began to displace conventional media and became the primary information distribution system. Social climbers bought with their ears, in other words, using rumor, hearsay, or tips, rather than making informed judgments about or establishing personal connections to an artwork. Enter market myopia, aided and abetted by technology.

CAMPBELL'S ANDY WARHOL POP ART 50TH ANNIVERSARY TOMATO SOUP CAN SET of Four, Released: September 2, 2012. e-Bay: December 25, 2024, US $92.50 or Best Offer.

Beyond its medical definition of nearsightedness, myopia has a profound cultural significance. The concept is intertwined with perceptions of education, intelligence, and social class. It was often associated with scholarly pursuits and intellectualism, owing to the stereotype "bookish" person (wearing glasses). While myopia became a mark of educational attainment and social status in some contexts, in others it was seen as a sign of physical weakness or over-civilization. The cultural meaning of myopia also extends into literature and art, where poor vision often serves as a metaphor for limited perspective or inability to see the bigger picture. This metaphorical use highlights how physical vision has become deeply connected to concepts of wisdom, understanding, and worldview in many cultures. Understanding market myopia in the art market is crucial because it helps identify potential blind spots in how artistic production is both valued and supported.

The cultural impacts of cell phones and digital cameras on the art world were quite profound. The immediacy of digital reactions changed how art was received and discussed. In short, a "see it, snap it, share it" culture emerged and transformed how people engaged with artworks. A sort of market myopia emerged, creating visual bias, rapid—often inaccurate—judgments, market distortions, geographic tunnel vision, and temporal shortsightedness. This myopia is clearly underscored in a December 2024 report by Artsy, an online art brokerage, that summarized a list of artists who had the most inquiries between 2020 and 2024. Artsy did not clarify if or how these inquiries related to sales, but the list alone accentuated consumer fixation on ten artists whose output has become consumable everyday commodities.

The summary reveals the narrow interests of the art audience. Their myopia is not only commonplace but also problematic. Foremost, there is an underlying interest in and emphasis on easily marketable formats and mediums over experimental or challenging works. This is accompanied by ignorance and neglect of art forms or styles that do not fit market preferences. Overvaluation of established artists with proven sales suffocates the markets for emerging talent.

“Artists with the most inquiries on Artsy, 2020-2024,” The Artsy Market Recap 2024.