mythologies and realities

Who’s who?

Christian Jankoski. Point of Sale, 2002, DVD and hree-screen video installation

Annually—if not more often—several print and online media publish lists of “top collectors” focusing on a few key criteria, like age, gender. sources of wealth, domicile(s), and types or varieties of art assets. Increasingly, the collectors are an aging population of North Americans and Europeans, reflecting the contraction of the art market and stagnation in the overall community of collectors.

Lists—like prizes—are generally nonsensical, reminding us of Malcolm Forbes quote, "He who dies with the most toys wins.” Rarely do these lists specify philanthropic relationships, if and where they exist, nor do they describe the level and degree to which collectors are actively engaged in the art market. Without question, many prominent collectors are active traders, even flippers, buying and selling art via many, largely private, market channels.

“Who’s who” lists reinforce the myth of middle class collectors. The art market was transmogrified in post-War United States. While collecting had always been the domain of the über wealthy, the professional classes—the educated, upper-middle class—became increasingly engaged at the same time as the proliferation of artists, expansion of number of galleries, and creation and growth of museums. The average cost of a painting by an emerging artist in 1980 was $500, which is nearly $2,000 in 2024. The average cost of a painting today is $25,000, a princely sum given that the average annual pre-tax salary in the United States approaches $60,000,

Collectors in contrast

Herbert and Dorothy Vogel have been characterized as New York’s “proletarian collectors.” Herb was a clerk, sorting mail for the United States Postal Service until his retirement in 1979. Until she retired in 1990, Dorothy—a dual-degreed librarian—worked for the Brooklyn Public Library. Reputedly, the couple used Dorothy's income to cover their living expenses. Instead of eating in restaurants or travelling, they used Herb's income to buy art, which peaked at $23,000, which roughly equates to $100,000 in 2024.

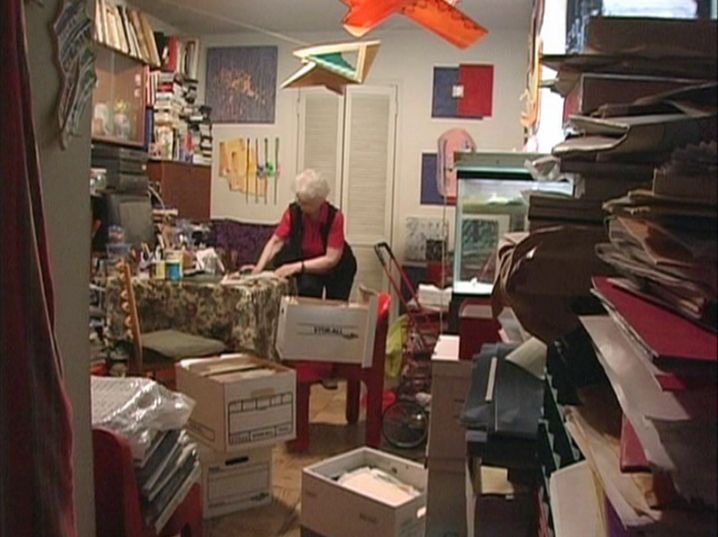

The Vogels had no children. They lived very frugally. They shared a rent-controlled, one-bedroom apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side with fish, turtles, and cats named after famous painters. The Vogels spent their free time methodically visiting museums and galleries throughout New York City, befriending artists, touring their studios, and regularly acquiring works of art directly from artists. By the 1990’s they were fabled gallery-goers in SoHo, and were frequently seen eating their brown-bag lunches on gallery steps.

The Vogels were shrewd negotiators, and sometimes made purchases on credit or payment plans, and even occasionally exchanged pet-sitting services for works of art. Over a fifty-year period from 1962-2012, the Vogels amassed a collection of over 4,782 works, which they lent and displayed, but also stored in closets and under the bed. (See images below.) Their art habits could be mistaken as hoarding.

Herb and Dorothy began lending their collection to art exhibitions in the 1970s, which underscored their well-earend reputation as discriminating and generous collectors. By the late 1980s, their collection was so large that the Vogels initiated plans for philanthropic donations. They were courted by many institutions, but the Vogels ultimately chose the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC. They were particularly drawn to the Gallery’s dedication to public service, its free admission policy, and its practice of barring sale of donated works of art. These characteristics appealed to the Vogels as both as art collectors and as retired public servants.

The materials in the NGA collection span the years 1948–2020. (The bulk of which dates between 1962 and 2004.) The bounty consists of nonaccessioned works of art, artists’ books, correspondence, newspaper clippings, monographs, photographs (prints, negatives, and 35mm slides), video tapes, audio tapes and reels, monographs, exhibition catalogs, inventory and object lists, legal and financial records, posters, and other documentary materials. In short, a near complete archive. There are two other major inventories of Vogel-abiliia. Vogel 50x50 brings together 2,500 contemporary artworks that were distributed throughout the nation as part of The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection: Fifty Works for Fifty States gift. Currently, 2,612 artworks have been published on the site. The Vogels also donated 47.5 linear feet of boxed archival materials from to the 1960s to 2009 to the Archives of American Art. Few collectors have been as generous and meticulous.

The catalog of The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection | Fifty Works for Fifty States can be downloaded as a PDF.

Rosa and Carlos de la Cruz were almost polar opposites of the Vogels. They were born in pre-Castro Cuba to cultured and “well-accommodated” families. Rosa’s grandfather was a famous architect, and Carlos´ family valued and collected art. Their story began in Havana where they met as teenagers. In 1960 they moved with their families to the US, fleeing from Castro's political regime, and got married in 1965. Before settling in Florida, in 1975, the couple lived in Philadelphia where Carlos attained an MBA from Wharton, and then moved to New York and then Madrid, where they raised their 5 children. As years passed, Carlos was chair and Rosa was treasurer of CC1 Companies, a $1-billion-per-year bottling and distribution empire, the brands of which included condensed milk, Coca-Cola, and Anheuser-Busch.

The couple was well-informed about art, and Rosa was especially drawn to Picasso and Van Gogh. They started collecting on a significant scale when they were financially able to do so. They considered focusing on modern Latin American art, but in 1992, their orientation of their collection changed radically when they acquired a work by Félix González-Torres, a gay Cuban-born artist-émigré. They were inspired by the artist´s conceptual language, which became a foundation for their decision to focus on contemporary international art.

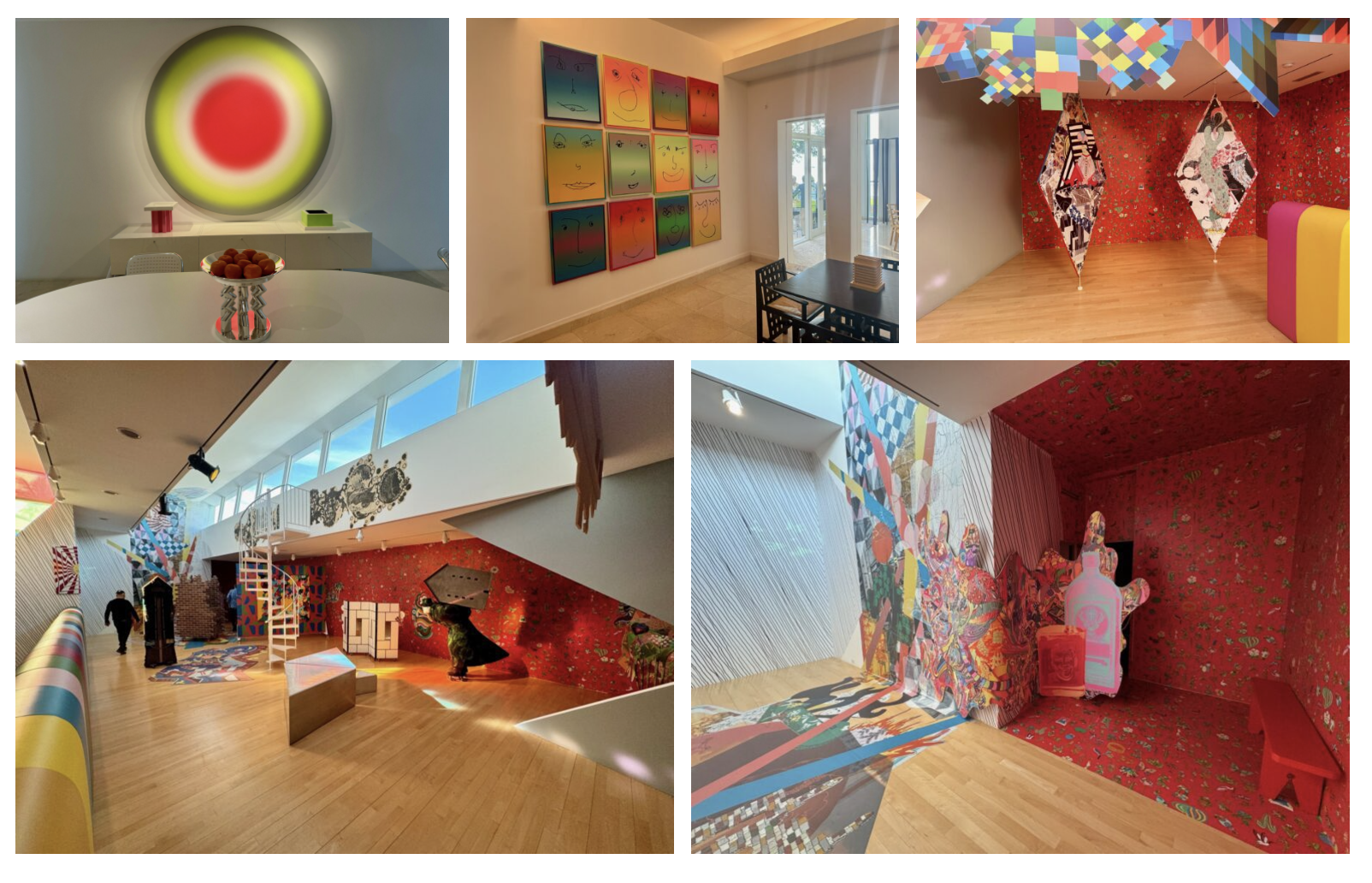

Before the opening of the de la Cruz Collection in Miami's Design District in 2009, the couple's art was displayed in a pristine, uncluttered mansion in Key Biscayne. Art ruled the house. Rosa once said, “We do not place furniture against our walls. Carlos and I have always lived with art in a way that for some may seem unconventional and [we] do not consider artworks decorative objects.” They adapted their home to be function like a gallery, minimizing furniture. and painting the home’s interiors white.

Peter Doig. Study for Night Fishing, 1999, oil on canvas.

For several years, Rosa and Carlos hosted an annual open house during Art Basel Miami Beach. At one such reception, Rosa described her auction purchase of Peter Doig’s Study for Night Fishing as a birthday gift for Carlos saying, “I can’t believe the stupid person who sold this painting.” As attendees, we nudged her and said (with a smile) “Greg and I were the stupid people. We sold it without hesitation or regret. Why? First, it was a study, not a major work. Second, our approach is to own several works by an artist, not one or two.” I paused and then added, “Our ROI was nearly 2,000 percent. Thank you.”

Rosa was unquestionably the dominant force behind the museum, replete with a curatorial staff and community programs. She relied on a collection of US and German galleries and over time used a few art advisors, minimizing risk. It was not a collection of discoveries.

Plot twist.

In June 2024, Rosa de la Cruz died at age 81, following an extended battle with an autoimmune disorder. Her 30,000-square-foot museum was permanently shuttered the day she died. The website is a digital grave stone. Carlos said he did not want to burden his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren with the collection's care and operating costs. He added that the collection was Rosa's passion, and that it was "different now" without her.

The collection was once valued at over $100 million, but as the art market has contracted recently, so has the collection’s value. Over 200 artworks were consigned by Christie’s, and the first sale achieved $34 million. (The estimated total for the sale was $30 million.) The status of the de la Cruz archives are unknown. As for the shuttered museum, The Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, purchased the exhibition space for $25 million in October 2024.