the good, the bad, and the mediocre

Logan, Josephine Hancock. Sanity in Art. Chicago: A. Kroch, 1937.

In 1936 Josephine Hancock Logan, the wife of a leading patron of the Art Institute of Chicago, founded the Society for Sanity in Art, Inc. movement. It opposed modernist art movements and advocated for more traditional, representative art forms.

Chapters sprung up around the country, influenced by her manifesto, titled Sanity in Art. Logan maintained “A madness seems to have swept over the world since the Great War.” Logan continued, “A destructive atavistic violence that stopped at nothing and held nothing sacred. The cuckoo of publicity had laid the egg of a modern dodo bird in the hard old nest of art . . . ” Hence, her evangelistic crusade was to remove “modernistic grotesqueries” from American museums and homes and “destroy the false gods” of surrealism and Dadaism. The review of the book in the March 27, 1937 issue of TIME magazine underscored her “bitter complaints.”

Definitions and criticisms about bad art haunt art circles and the art media. Most often, bad art is misconflated [misuse intentional] with mediocrity. Bad art is stimulating, even annoying. Mediocre art is numbing, reflecting stagnation, poor decision-making, and a lack of innovation.

How good is bad art?

In 1978, Marcia Tucker, the founding director of the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, mounted an exhibition titled "’Bad’ Painting.” This significant show challenged conventional notions of artistic skill and scorned “the standards of good taste." In other words, "‘Bad’ Painting” was an ironic title for “good” painting.

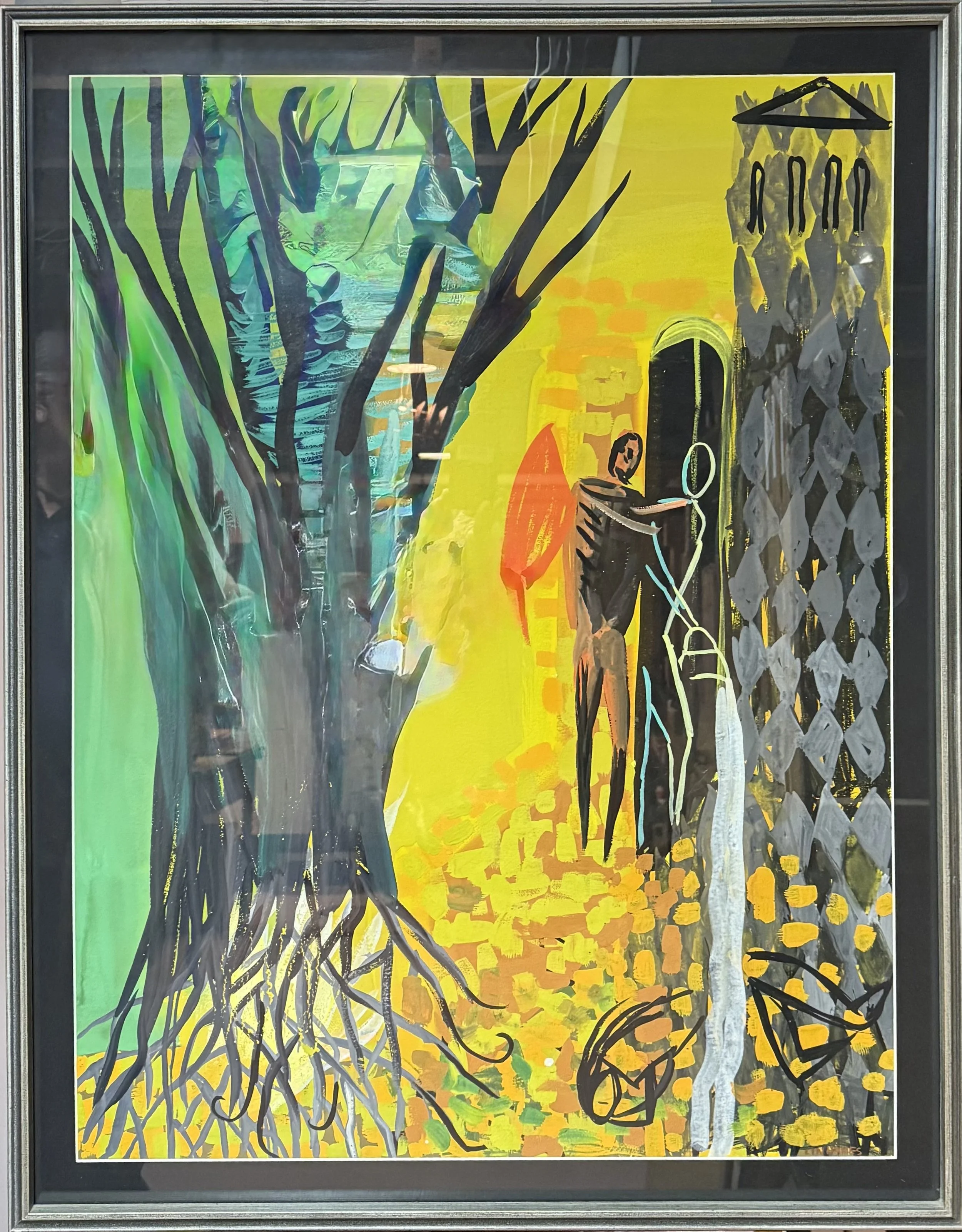

Judith Linhares. Dream Angel, 1982, gouache on paper.

Tucker elevated artists who were working against the dominant minimalist and conceptual art trends of the time. She featured works by artists—for example, Joan Brown, Joseph Hilton, Neil Jenny, and Judith Linhares—who deliberately rejected traditional standards of “good” (generally conventional) painting techniques in favor of more expressive, raw, and sometimes intentionally crude approaches. The fourteen painters in the exhibition embraced figuration, narrative, and personal expression, when such approaches were often dismissed by the mainstream art market. (They are once again in vogue, while the market for minimalism has waned.)

One frigid Berlin night some 20 years later, Barbara Weiss, the late gallerist, hosted a post-opening dinner party. The conversation detoured into a heated argument about bad art. Weiss recalled an argument she had with a German journalist about the subject. Like Tucker, Weiss argued that bad art was good because it was engaging and provocative, and that the art market was buried in mediocrity. She gave an example.

An American artist on a travel stipend in Berlin dropped off a portfolio of abstract paintings on paper. Weiss flipped through them, unimpressed, but she left them on the corner of her desk. Yes, the work was bad, but it was annoying enough that the gallerist revisited the portfolio several times before inviting the artist to participate in a group show. Representation followed, and today, the artist is shown by multiple galleries, has had solo museum exhibitions, and has a solid commercial market.

The amount of mediocre art is staggering. Weiss even suggested it represented 80 percent of the market. Worse yet, much of it is referred to as “art fair art.” (See jargon and jabberwocky.) It undermines originality by relying heavily on clichés, overused themes, or direct imitation without adding new perspective. It sometimes shows technical competence—especially in abstract and process-based work—but demonstrates no creative risks or personal voice. It follows trends without understanding or reinterpreting them and seems to exist primarily to match furniture or fill wall space. It is career-limiting.

What's considered "bad" in one context or time period might be revolutionary in another. Historical context—however brief—can transform our understanding of previously dismissed work. In short, the boundaries between provocatively "bad" and genuinely bad are often blurry.